The Piper's Corner:

Understanding Bagpipe Music

by Peter Walker, PVSFC

Board Member

Fiddlers often find

themselves playing bagpipe music. As a piper myself, I can't for the life of me

think why! Seriously, there are a lot of good marches, and plenty of other

tunes and airs that are worthy of being in a fiddle player's repertoire (and

many more that...well, my mama said if you can't say something nice...). In

this series of columns, I hope to shed some light on the whats, whys, and

wherefores of bagpipe music, so this music becomes less opaque to the fiddler.

In future installments, I intend to address bagpipe ornamentation, principles

of stress (called pointing), different types of bagpipe tunes, and eventually

the nature of piobaireachd. But for now, we'll start with two simple concepts.

"The Nine-Note Party

Favor"

At my first bagpipe

lesson, this is what my instructor called the thing. He even denied it was a

musical instrument at all - no rests, no dynamic range, a single key signature.

But he was just making a point - you'll have bagpipers (usually people who've

never touched another instrument) claiming it's the pinnacle of difficulty and

expression in music. Clearly these people have never seen a pipe organ played!

But really, it is a nine-note party favor, one that comes with a colorful

costume.

The nine notes of the

bagpipe form a simple Mixolydian scale with a flattened 7th on top and bottom.

We write these notes G, A, B, C,

D, E, F, G, and A. I boldfaced the first A because it's the tonic. Now,

strictly speaking, that C and F are sharp, but for some reason it's suppressed

in printed pipe music. Don't be fooled! Add two sharps in your head when you're

looking at tunes in pipe collections. Old pipe music was largely dual-tonic;

that is, often it would have a phrase in A, followed by a phrase in G (think

"The Devil in the Kitchen"). Sometimes this role was reversed (G

Lydian mode, like "The Bob of Fettercairn"), or the two keys would be

in B minor and A (like "The Ale is Dear"). The scale of the bagpipe

is ideal for this kind of music, but it is pretty limiting to the modern

ear. Recently, more and more music has been written for the bagpipes in

the key of D major, forcing a retuning of the chanter's D (which used to be

sharp relative to most intonation systems).

So every bagpipe tune you

see will have these nine notes. If you see a tune with more than these, it's

already been adapted for fiddle. Similarly, tunes and songs adapted for the

bagpipes will be "squished" to fit this scale. Many is the tune in A

major that saw its G# (e.g., "Highland Whisky" flattened to fit the

pipes And others saw a high B turned into an ornament, or a low F-sharp turned

into a low G. But wait! I've been fibbing to you. Because though pipe music is

written as if it's in the key of two sharps, it's now played somewhat sharp of

three flats! So our scale really is 25 cents sharp of Ab, Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb.

Why do we write it one way

and play it another? It is because the pitch of the instrument has come up in

the last couple of centuries relative to most other instruments. When Joseph

MacDonald - a trained violinist who studied the pipes as a young adult - wrote

his manuscript on the Highland pipes in 1759, he felt the scale of the bagpipes

was close enough to call its tonic "A." But A drifted pretty high in

Victorian times, with the "Queen's Hall" standard, A became more than

half-way to what we now call Bb. When it drifted back down, the Highland pipes

stayed up there. For a while, then, it was in vogue to play with brass bands,

so Bb was a perfect key for the instrument. But that fell out of fashion at a

time when competition judges and pipe majors were looking for a

"brighter" sound for bands. So mistaking "sharp" for

"bright," up the pitch climbed almost to halfway between Bb and B.

Sanity has crept over the community in the last few years, and now it's just

sharp of Bb now. At the same time, a movement to "play in A" began,

and so you're seeing more solo and "Celtic" pipers having chanters

made in concert A to be

more fiddle friendly. Sorry we can't do more about the volume!

One more slight fib must

be revealed. It's really not nine, but more like eleven and a half notes. Many

chanter/reed combinations can play a note close to C-natural and F-natural as

well, and a very few can play something close to G#, with an alternate

cross-fingering. Even fewer can play a high B! But the tuning on these notes is

usually suboptimal, so they're better for passing tones than notes one holds

on. And formal bagpipe music never uses these notes; woe upon you if you

actually play "Lochiel's awa' to France" in a proper A minor in

competition.

Next time, watch for

"Shake your Doublings: Emphatic Ornaments, What They Look Like, What They

Sound Like, and How to Imitate Them."

The first time fiddlers

crack open a bagpipe book, they are often struck by the sheer number and

complexity of grace notes. "How do you read all of these?" is a

common question I hear. The simple answer is: I don't. I play all of them, of

course, but I don't read them as individual notes. Bagpipe ornaments come in

only a few, highly formalized figures, and over the next few columns, I hope to

demystify them a bit, explain how they're executed, describe their musical

function, and suggest possible means for a fiddler to interpret them.

Do You Hear an Echo,

Grace: The Simplest Ornaments

The basic ornament of

bagpiping is a single grace note. The grace note is effected by the very brief

lifting of a single finger; this is in contrast with melody notes, which use

more complex fingerings. Because of how it's executed, a grace note can only be

played at a higher pitch than the melody notes it's played between. But it can

also be almost imperceptibly brief. Any note except low G can be used as a

grace note, but by far the most common are the high G, D, and E, a fact that

makes the music easier to read. High G is overwhelmingly the most common, and

it is prevalent on downbeats, especially the first beat of a measure.

If it's necessary to play

multiple grace notes in rapid succession on a low melody note (low G through

C), the pattern is often G-D-E, or if necessary a G-D-E-D pattern. The reason

for this is ergonomic. It's easier to play multiple grace notes fast if you

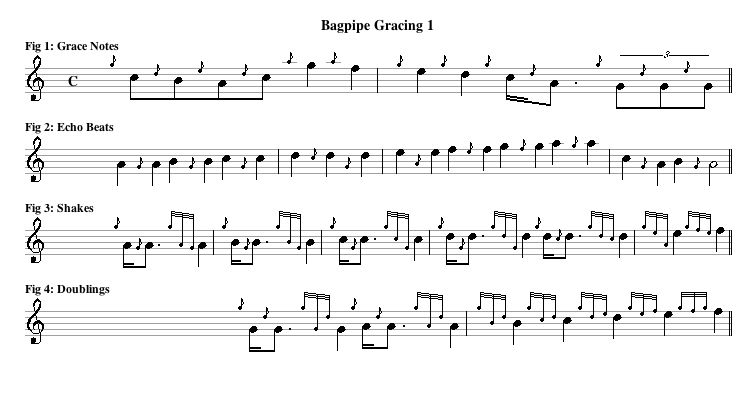

have a practiced sequence of fingers to work through. Figure 1 shows a

representative sample of grace note figures. The first bar demonstrates a

G-D-E-D pattern and high A grace notes. The second bar features some G grace

notes, a typical G-D pattern in a snap (called a "tachum"), and a

G-D-E pattern seen in a jig-style triplet.

Similar to the grace note,

and notated identically, is the echo beat. Where grace notes briefly lift a

finger to play above the melody pitch, echo beats briefly slap down

fingers to play a brief moment of lower pitch. For notes lower than D, the echo

beat is low-G. For E, the echo beat is low A. For notes above E, the echo beat

is the note below. D is a special case: it has two echo beats, a

"light" to C, and a heavy to G. Figure 2 shows a number of examples

of echo beats. Note that a gracing can be identified as an echo beat because it

is lower in pitch than the two adjacent melody notes. While much rarer, echo

beats are used similarly to grace notes, but only rarely at the start of a bar.

They have a more percussive sound than a grace note, and are often used to go

from one note to a lower one, especially from B to low A (the echo beat between

them being a G), and there especially at the end of a phrase.

Grace notes and echo beats

are principally articulatory in nature. That is, their primary purpose is to

create a stronger separation between notes. An open-end chanter like that on the

Highland pipes is necessarily a legato instrument. Grace notes permit a more

staccato-like sound to be achieved. Most simple gracing of these two types

occurs on a down beat, though they will less frequently be seen on an upbeat,

and sometimes to articulate the two notes in a Scottish snap-like figure (see

Figure 1).

A fiddler looking to

replicate the sound of a simple gracing may use a tap on a note change, though

usually a brisk change of bow direction (as opposed to a slur) achieves an

equivalent level of articulation.

Shake Your Doublings:

Two-Pulse Emphatics

Building on the simple

gracing is a family of two types of compound ornament: shakes and doublings.

Both are formed similarly. On the note change (usually on the downbeat, but

sometimes the upbeat), a G-grace note is sounded. Some time after a brief

interlude of the melody note, a second grace note or an echo beat is sounded,

and then one holds the melody note for the remainder of the nominal value of

the note. In the case of a shake, the second pulse is an echo beat (Figure 3),

and in the case of a doubling, the second pulse is another grace note (D when

the melody note is G, A, B, or C; the note above the melody note for E and

F).

These ornaments normally

imply an accent on a note. As bagpipes can not play dynamically, doublings and

shakes are one mechanism by which stress is implied. Doublings are by far the

more common of the two. Shakes, on the other hand, tend to be associated with a

repeated note at the end of a phrase, especially in tunes in the key of D. In

the first few bars of Figures 3 and 4, I demonstrate how shakes and doublings,

respectively, are approximately played, and how they are actually notated in

bagpipe music. Having established the pattern, the remainder of the bars in each

figure show the bagpipe notation only. In both cases, note that the middle

grace note actually lasts a perceptible amount of time, while the initiating G

and subsequent grace note are ideally imperceptibly short.

Marches, even ones played

by beginners, can be thickly populated with doublings, and even a

few shakes. These ornaments appear complicated in print, and one wonders,

"how can you read them at tempo?" But shakes and doublings on a note

are always formed the same way, so a doubling on D is always a doubling on D,

and a shake on F always a shake on F. One need not read the ornament while

playing so much as recognize it, then execute the finger movements you've

drilled. In a sense, a piper shape-reads the ornament and plays by reflex. The

ornament is recognized as a 2-pulse emphatic by the first two grace notes, and

distinguished between a doubling and a shake by noting whether the third grace

note is higher or lower on the staff than the second grace (and melody)

note.

How might a fiddler interpret

these ornaments? The most literal interpretation would be to perform a tap on

the note change, and a second (delayed) tap a brief moment later: a double-tap.

However, as mentioned above, a briskly articulated bow change usually achieves

the same effect as the initial G-grace note, so a delayed tap is usually enough

to imply this type of ornament. How long should the delay between the note

change and the delayed tap last? Pipers speak of this in terms of the

"openness" of the doubling or shake. It depends on the tune's tempo.

Faster tunes like reels will see very "closed" doublings (with a

short delay), marches and airs might see more open doublings. But this holds

true: if the smallest basic note on which a doubling or shake might occur is an

eighth note, then the delay should be less than a sixteenth note, so that the

most open possible doubling will bisect the note it's occurring on.

Furthermore, with some exceptions, doublings and shakes should be

"balanced" in a given tune, or set of tunes of the same rhythmic

type. That is, if you're playing a set of 4/4 marches, all doublings and shakes

in all the tunes should be of the same size; and hence the delay in the delayed

tap would also be balanced across the tunes.

But what about shakes and

doublings to and from high G and high A? This and more, next time when we

discuss Advanced Emphatics: High A and Half-doublings, Fake Shakes, Jig Shakes,

and other oddities.

Half on the High Hand

In my last column, I

discussed basic articulatory grace notes, and the workhorses of bagpipe

emphatic ornamentation, shakes and doublings. But note that I only discussed

shakes and doublings up to the melody note F. What about the high G and high A?

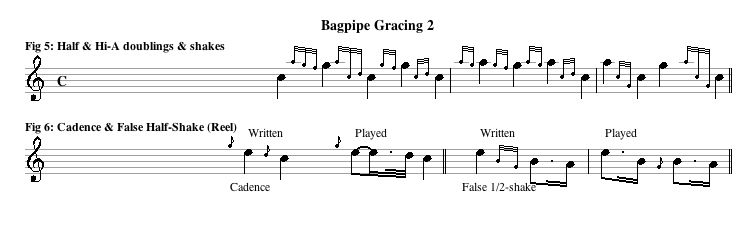

Well, these are necessarily special cases. As two-pulse emphatic ornaments

generally start with a G grace note, a note unavailable when playing notes

higher than F, these shakes and doublings must be formed differently. The

simplest case is shakes and doublings from high A to a note lower than F. In

this case, the initial G-grace note is simply left off. We call these

"half-shakes" and "half-doublings". Other than the missing

initial grace note, they are timed exactly as any other shake or doubling would

be. In the case where there is a shake or doubling from high G to a note

lower than F, there are two possibilities. Either one could, as with coming

from high A, perform a half-doubling or half-shake, or alternatively, one could

use a high A grace note in the place of the high G grace note that usually

initiates these ornaments. The choice is left to the composer or arranger,

and is indicated in the music. If the high A grace note is used, it's

called a "High A doubling or shake" or a "Thumb doubling or

shake".

In the case of going

to high G and high A, the situation is similar: to high A, one performs a

half-shake, and to high G one performs either a half-shake or a shake with an

initial high A grace note in place of the high G. The nomenclature, however, is

somewhat confusing, though. Though performed as shakes to high G and high A,

these are called "doublings". Figure 5 shows, in the first

bar from left to right, a high-A doubling from C to high G, a high-A

doubling from high G to C, then half-doublings to and from the same. The second

bar shows half-doublings from and to high A. The third bar shows a half-shake

from high A and a high-A shake from high G. For a fiddler, the most literal

translation of these ornaments is a delayed tap.

Cadences

In our last

installment, I discussed grace notes, simple gracings higher in pitch than the

melody notes they separate, and echo beats - simple gracings lower in pitch.

There is, though rare, a third category, called a "cadence", where

the melody is falling down the scale, and there is a grace note of intermediate

pitch inbetween. Cadences in "light music" (marches, airs,

dance tunes) are a holdover from piobaireachd, usually start on an E melody

note, and the cadence will typically be a D grace note. In this case, the

cadence acts like a very short melody note taken from the time of the previous

melody note. I've shown a cadence in the first bar of Figure 6. How they appear

in "light music" is different from how they're written in

piobaireachd, so we will one day visit cadences again.

Sometimes a Shake

Isn't a Shake

Once in a while, bagpipe

notation is sloppy, and one sees ornaments that aren't ornaments at all. One

prominent case of this is seen in the last two bars of Figure 6. In reels,

sometimes one will see a half-shake that comes from a note other than high G.

Though notated as such, this is not a half-shake at all, but rather an

idiomatic way of writing a melody then grace note. The second bar shows an

example of this as one might see written. If one were to literally interpret

this, one would play a quarter note E, then a half-shake on the B dotted

eighth, followed by an A sixteenth. But that's not what's meant. A half-shake

begins on the beat, but this "fake shake" ends on it! The third bar

indicates how it should be written; as a standard swung reel rhythm. How does one

tell the difference from a "fake shake" and a real half-shake? There

are two clues: first, the "fake shake" appears almost exclusively in

reels, and it is characterized by a half-shake that comes from a quarter note

that's not high G or high A.

In our last installment,

we began discussing some oddities in two-pulse emphatics like shakes and

doublings; we’ll wrap that discussion up here, and dip our toes in the waters

of our next subject: anticipatory ornaments

Sometimes a Doubling

Is A Triplet

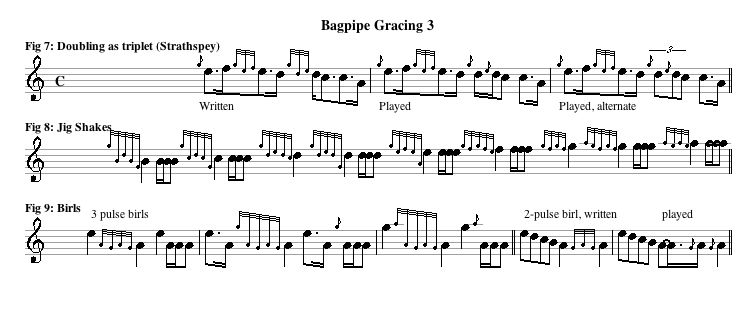

There's another wrinkle

that usually appears in Strathspeys, but occasionally appears in other tunes.

When a doubling is applied to a snapped figure (sixteenth-dotted eighth), the

intent is to form a triplet, similar in rhythm to a birl. Figure 7 shows an

example of this from the Strathspey "Susan McLeod". The first bar

shows how the tune is written, and the subsequent bars how it is played. Note

that the first doubling is a true doubling, while the second is a triplet. This

is the exception to the "all shakes and doublings should be balanced"

rule. In the case of a tune with both doublings and doublings-as-triplets, the

regular doublings should be played fairly closed, and the doublings-as-triplets

should resemble, and be balanced against, birls, which will be fairly open. Doublings-as-triplets

may be better performed by a fiddler with a birl-bowing rather than by taps,

though it takes some practice to change notes for the third pulse of the birl.

Doubling + Shake =

Birl

To a fiddler a birl is

simply a bow movement, so birls can be performed on any note, but to a

bagpiper, the birl is an ornament peculiar to the low A. Bagpipers have several

ways to perform birl-like rhythms on notes other than low A, and the Jig Shake

is one of them. A Jig Shake is a doubling followed by an echo beat to create a

three pulse emphatic. One can almost see it as a doubling and shake combined.

The Jig Shake is a newer ornament, similar to the Irish piper's cran, and will

be seen mainly in recent compositions or arrangements, like those of Gordon

Duncan. Figure 8 shows Jig Shakes from B on up, including two options for D and

high G, paired with the equivalent birl the fiddler would play.

Speaking of Birls…

This leads us to the

actual birl. Bagpipe birls are executed by playing a low A, and then twice

swiping the right pinkie over the G hole in rapid succession. This is why

bagpipe birls sound so distinct. I have illustrated several bagpipe birls, as

written and played, in the first three bars of figure 9. Bagpipers call these

“three pulse birls”, as there are three distinct A melody notes, and are

identical in rhythm to those with which fiddlers are familiar. Sometimes, as in

the second or third example, the birl is initiated by a high G or high A grace

note, especially, as in the second example, one is needed to separate a

previous A from the birl proper (as in Crossing the Minch and Devil in the Kitchen), but also to simply make a crisper beginning to

the birl.

The last two bars show

a different beast entirely! This is what pipers call a two-pulse birl.

Mechanically, it is executed identically as the three-pulse birl, but the

initial A is not part of the birl, but part of a melody note. Very common to

end phrases, this sort of birl is anticipatory - that is, the movement

completes on the beat. As the last bar of figure 9 shows, this sort of birl

creates a particular rhythm that might be sung Ah… ta-Dah, with the capital

letters falling on the beats.

This is just the first

of several bagpipe ornaments that end, rather than start, on the beat. Next

time, we discuss the world of anticipatory ornaments in: Get a Grip!

In our last several columns

(see previous columns at http://www.potomacvalleyscottishfiddle.org/the_pipers_corner/),

we discussed emphatic ornaments; that is, ornaments that either occur on a

beat, or begin on them, such as the shake or doubling, or most occurrences of

the simple grace note. But in our discussion of birls, we came across a version

of that ornament that, rather than beginning on the beat, ended on it.

We call these ornaments

“anticipatory”, and they make up a major part of the bagpiper’s repertoire.

Get a Grip

In light music (aka, marches,

dance tunes, and slow airs, as opposed to piobaireachds), the fundamental

family of ornaments of this type is called a “grip”. It is so named,

presumably, because to execute them, the piper “grips” the chanter, closing all

the holes and going down to low G, and then executes one or more gracenotes

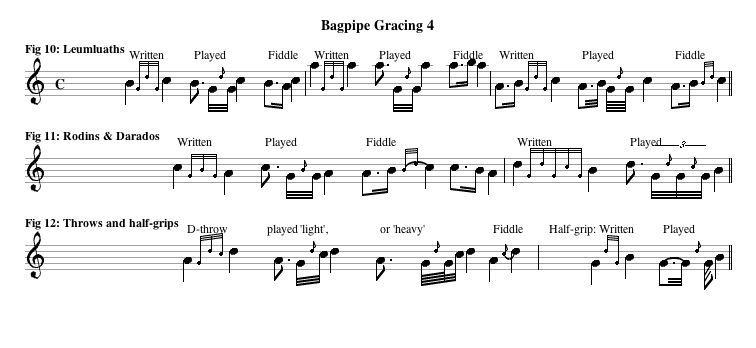

while on low G, before returning to the next melody note. Figure 10 shows the

most basic forms of grip.

The first example gives a

grip from B to C. This form, called a leumluath, consists of a D grace note bisecting

two low Gs; the total length of the grip being approximately a sixteenth note,

each low G in isolation must then be approximately a thirty-second note in

length. The second example is of a grip from high A to high A, formed

similarly. Both of these would be examples of a very “open” grip. In reality,

they would be played tighter; the low Gs shrinking, and the preceding melody

note expanding to fill the time.

Some contexts require an

even smaller grip. Bar three of figure 10 shows a grip occurring in a run up to

a melody note. This figure is quite common in simple time marches, like Leaving

of Liverpool. In this case, the grip is stealing its time from a sixteenth note

B. So in actual execution, the B must become approximately a thirty-second note

to make room for the grip, and each of the Gs in the grip will become a

sixty-fourth note. When a grip is this closed, it begins to sound like a

ripple.

How is the grip to be

interpreted? In the first two bars, the grip is essentially substituting for a

melody note around a sixteenth note in length. I tend to interpret grips of

this form in this way on fiddle, and play an adjacent melody note in place of

the grips. For example, in bar 1, I might try an A in place of the grip; in bar

2, a high B. Though one loses the double-pulse ripple effect of the grip simply

playing a single melody note, its melodic function is preserved. If one wanted

to be more literal, one could subdivide the note with a tap. In the third bar,

the grip has taken on a purely ornamental function; it is creating an emphasis

on the following melody note. In this instance, I would play a hammer-on to the

following melody note in place of the grip, or possibly a hammer-on followed by

a tap, to achieve an equivalent effect on fiddle.

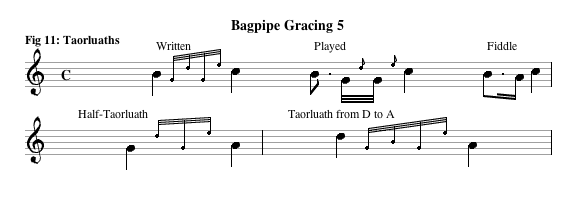

The first bar of figure 11

shows the simplest variation on a grip. Grips can occur from any note to any

other note, but their form changes in certain instances. For example, there is

no grip from low A to low A in light music. Furthermore, when executing a grip from

D or C to low A, or from D to E or higher, an alternate form is used. In this

alternate form, often called a “rodin”, a B grace note is used to separate the

two low Gs in the grip rather than a D grace note, but the ornament is

otherwise executed identically. I tend to interpret the rodin the same way I

would a leumluath in the same place. A more interesting variation is the

“darado”, a triple-pulse grip that occurs from D or C to B, shown in the last

bar of figure 11. The darado is sometimes used, not as an anticipatory

ornament, but as the equivalent of a birl on B.

When a grip is performed to

D, the form is known as a D-throw, illustrated in the first bar of figure 12.

The more elaborate form, known as a heavy D-throw, is essentially a leumluath

to C, which then serves as a hammer-on to D. The “light” form of the D-throw,

which may well be the more historical form, omits the second low G in the grip.

The D-throw is usually played very closed, as a ripple, and is almost never

played as a substitution for a melody note. In either case, the “light” form is

what is usually written, regardless of what is played. As a fiddler, I tend to

translate the d-throw as a hammer-on from C-sharp to D.

Grips can also come from low

G. Since the first note of the grip is already on low G, it is skipped, and

only the last portion of the ornament is played, as shown in the last bar of

figure 12.

The term leumluath refers to

the name of the variation in piobaireachd where this ornament, plus a

connective note, separates the theme notes. Both the rodin and darado are

comparatively rare ornaments in light music, and their names are from the

canntaireachd (sung form of piobaireahd) for these ornaments. Throws, in the

piobairechd idiom, are a family of ornaments unto themselves – more on that

later!

Taorluath – (Almost the)

Biggest Ornament

In previous sections, we

have discussed anticipatory ornaments, like the 2-pulse burl, and the family of

grips and Leumluaths. The final common ornament in the “light music” portion of

the Bagpipe repertoire is called the Taorluath, shown in figure 11. Possibly a

corrupted form of the Gaelic for “twice quickly”, this ornament is closely

related to the Leumluath but uses an E grace note to transition between the

second low G in the ornament and the next melody note. The second E grace note

gives this ornament a more chirpy, distinct sound than the leumluath, but the

distinction is subtle. Because of the E grace note, a Taorluath can not go to a

note higher than D, although in practice, Taorluaths only go to melody notes

below C, though they may start from any melody note. In the singular case of a

Taorluath from D to low A, a B grace note, rather than the usual D grace note,

is used to bisect the low G in the Taorluath. It is also possible to play a

half-Taorluath from low G, as with a leumluath or grip from low G.

The Taorluath is generally

used emphatically, though it can be often interpreted in a semi-melodic

capacity, especially in compound time tunes. This ornament is also used frequently

to separate two notes of the same pitch. And it’s a very common ornament in

piobaireachd, with whole variations named after this ornament.

There is another ornament,

called the Crunluath, and high hand throws, that are used almost exclusively in

piobaireachd, and we will bisit them another day. For now we have all our

pieces to play light music. Next time, we’ll look at a bagpipe tune and put it

all together!

Putting it All Together

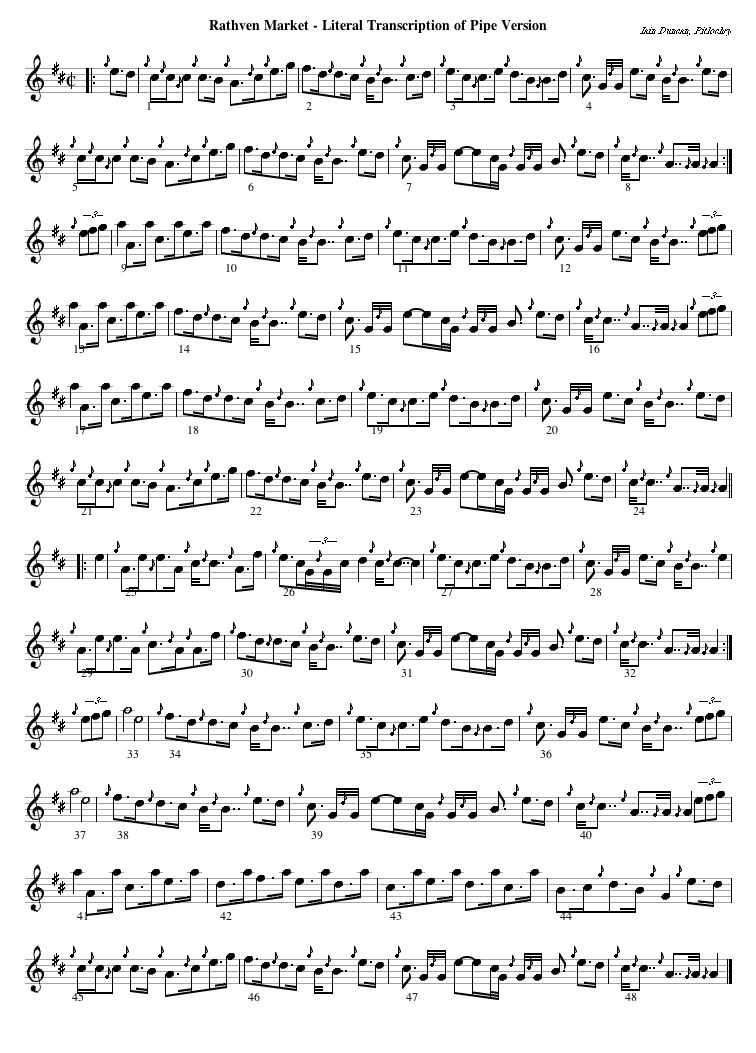

For the last several

columns, we’ve discussed the range of bagpipe ornaments, contrasting how

they’re written with how they’re played; but until we put them into context,

it’s all squiggly lines on a page. So it’s time to start looking at a few

bagpipe tunes. Starting next fall, each column will start with a basic tune,

beginning with 4/4 marches, and break down the usage of ornamentation. But I

though I’d send you off for the season with something fun. The tune I’ve chosen

to look at is a hornpipe called Rathven Market, by Iain Duncan of Pitlochry. It’s been included

as an insert to the newsletter; on one side the pipe version as published, and

on the back, the literal interpretation of the rhythms and a fiddler’s

interpretation.

The tune was written in

2/4, but I’ve changed it to cut time to make it easier on the eyes. Note that

the swing is all literally expressed – that’s because pipers have two forms of

hornpipe; what they call a “round hornpipe” is what we fiddlers would call a

double reel. So to distinguish the two, the traditional hornpipe is written

with swing. I personally prefer this tune in the slower Newcastle style of

hornpipe playing. It’s unusual for a bagpipe tune in that it is in A major;

avoiding all G notes except for as passing tones, and a single excursion into a

G-chord at the end.

So let’s look at the

first part; most of the noteworthy ornamentation in this part, especially its

end phrases, are repeated throughout the tune. In bar 1, we see a jig shake on

a quarter note C. As we will recall, a jig shake divides a note into three

parts; so this ornament is to be interpreted as either a triplet or a birl on

that C. The rest of the bar contains single grace notes; these can be included

or omitted as the fiddler prefers as taps on the note change or beat – though a

sharp bow attack is all that’s needed to imply the chirp of a single grace

note. In the second and fourth bars, we see doublings on a quarter note B. As a

fiddler, I tend to approach those as a delayed tap on B; executing the note

change, and a brief time later, tapping the 3rd finger on the

string.

The 4th bar

also contains a grip from a quarter note C to a dotted eighth note. The

prevailing rhythm in a dotted hornpipe is dotted eighth-sixteenth-dotted

eighth-sixteenth. Since the grip is an anticipatory ornament that takes its

time from the previous note, one might suspect that it’s simply filling in the

role of a missing 16th note. And that’s the best interpretation, I

think; I would render this passage as a dotted eighth C, sixteenth D, to the

dotted eighth E.

The 5th and 6th

bars begin similarly, and bar 7 contains a grip identical in context to that in

bar 4, and I interpret it identically.

But what about the beast

of an ornament at the end of bar 7? That’s a darodo, a unique member of the

grip family. Not only does the darodo have three pulses (rather than the usual

two), in many contexts, it straddles the beat. Here, the beat occurs on the D

grace note; leaving one semi-melodic G before the beat, and two semi-melodic Gs

after. The first G takes its time from the sixteenth note C before; both

effectively becoming thirty-second notes. After the beat, then, there are two

thirty-second note Gs before the B, which must now (because of the time it’s

lost to the Gs in the darodo) must become a dotted eighth note. What does a

fiddler make of this? I would tend to interpret that figure, starting from the

E before it, as a dotted eighth E, a run of two 32nd notes from C to

B, and then a tight birl on B.

This brings us to the 8th

bar of the tune: a doubling on C followed by two As separated by a two pulse

birl. The doubling I again render as a delayed tap, while the two pulse birl,

being anticipatory, I recast as a dotted eighth A, a sixteenth A, leasing to

the quarter note A.

And that’s most of the

tune right there; since last two bars of the first two lines are repeated in

almost every part, except for the fancy ending. Because of this recycling,

there are only a couple more noteworthy moments in the tune for ornamentation.

Note all the sixteenth note high-As in the 2nd part (and their

reprise for the fancy ending of the 4th part). These are an example

of the “disappearing high A effect”, where a sequence of very short high-A

notes effectively blend into the drones, and seem somewhat inaudible. This

creates the illusion of rests. As a fiddler I might play the sixteenth note

high As quietly (maybe not at all sometimes!), and emphasize the dotted eighth

melody notes.

In the third part, we

see in bars 25 & 26 doublings on C, which I would render as a delayed tap;

and in bar 26, a d-throw, which I would interpret as a hammer-on from C to D.

And that’s pretty much it. Again, treat as many or as few of the single grace notes as you like as either sharp bow attacks or simple taps on the note change, and happy hornpiping!

"3/4: When the First

Beat is a Pickup"

When it comes to bagpipe

marches, everything is about the down feet, not the down beat. These marches

are marched to. In formation. With other pipers, and drummers even. And they

have to move together. It's all real simple. For a a quick march, the pipe

major cries, "Right. Quick. March." and you start walking to that

cadence, left foot first. Left, right, left, right. The drums immediately begin

with four beats of rolls on the first beat. On the fifth beat you strike in

your drones. On the seventh beat you play what's called the "preparatory

E" on the chanter, and the ninth beat starts the first bar of the tune. If

there is a pick-up, it's taken out of the time of the preparatory E, so that

the first beat of the first bar is the ninth beat since you started marching,

always on your left foot. As importantly, you stop playing on right foot.

Always. Even when marking time (marching in place). Even at rest.

This is all well and good

for tunes with an even number of beats per measure. But what about a 3/4 march?

Two very popular tunes of this type are The Green Hills of Tirol and Lochanside. Each bar contains a heavy beat, a light beat, and what's usually a

pick-up to the next bar, meaning the last note of the tune would be the second

beat of the last bar. If you were to play this as I describe, you would end on

the left foot. That won't do! So we've got to start the tune a beat later

somehow. Now, a sensible person would tell the pipers, "In the case of 3/4

(or 9/8) tunes, there's an exception. It's two beats of preparatory E plus the beat of pickup, instead of minus, and you start

the first bar of the tune on your right foot". But that involves math. So

pipe tunes are written so that the first beat of every bar is what should be

the pickup in the previous bar. Look at one of the tunes I mentioned in the

fiddle club collection. Look at it from a phrasing standpoint. The heavy beat,

from the standpoint of the melody, is the second, not first, beat of each bar. This is completely

contrary to the meter or 3/4, and it's entirely designed to get you to end the

tune on the right foot, if it begins on the left.

Now try playing one of

these tunes as written, but making the first beat of every bar the heavy beat.

Sounds strange, forced, doesn't it? It should! Now make the second beat of each

bar especially heavy. There, that's it. I suppose we should be writing those

tunes for fiddlers and other musicians with the pick-ups in their proper place

- but the horses left that barn long ago.

We left our survey of bagpipe music last year with the notion of putting the

ornaments together into a tune. This year, I'm going to present various types

of bagpipe tune, demonstrate a few, and show how the ornamentation and idiom

of the instrument come together to create the melody, and how a fiddler might

try to capture aspects of "pipey-ness" in a performance.

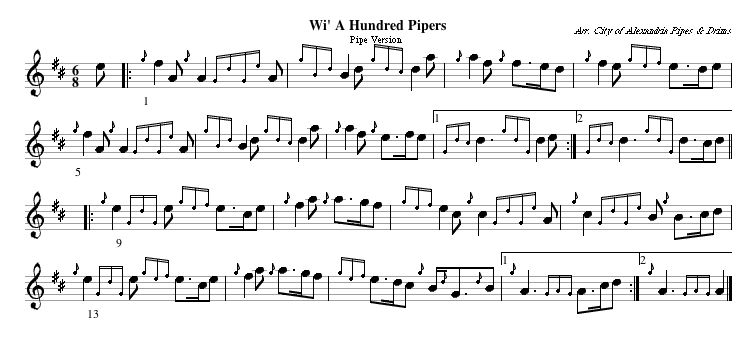

We'll begin with the 6/8 Quick March. Many of these tunes are sped up to become

jigs, but we'll focus on them in the march context for now. Compound time tunes

are a good way to begin in that there is very little flexibility in the

interpretation of time. There are three prevailing rhythmic figures in a 6/8

quick march, which my own pipe major has us sing as vocables: the dotted quarter

("ah"), the quarter-eighth ("dai-do"), and the dotted eighth-sixteenth-eighth

("rum-pa-di"). Other figures, where they may appear, tend to be one of these

rhythms in disguise. And they're always played literally as written. The tune

I've chosen to explore is "Wi' a Hundred Pipers". We've had this in A-major in

fiddle club before, and it takes advantage of the wider range available to the

fiddle. I will give the tune in within the pipes' range, D-major in the first part

and A-major(ish) in the second part. Here it is, as played by the City of Alexandria

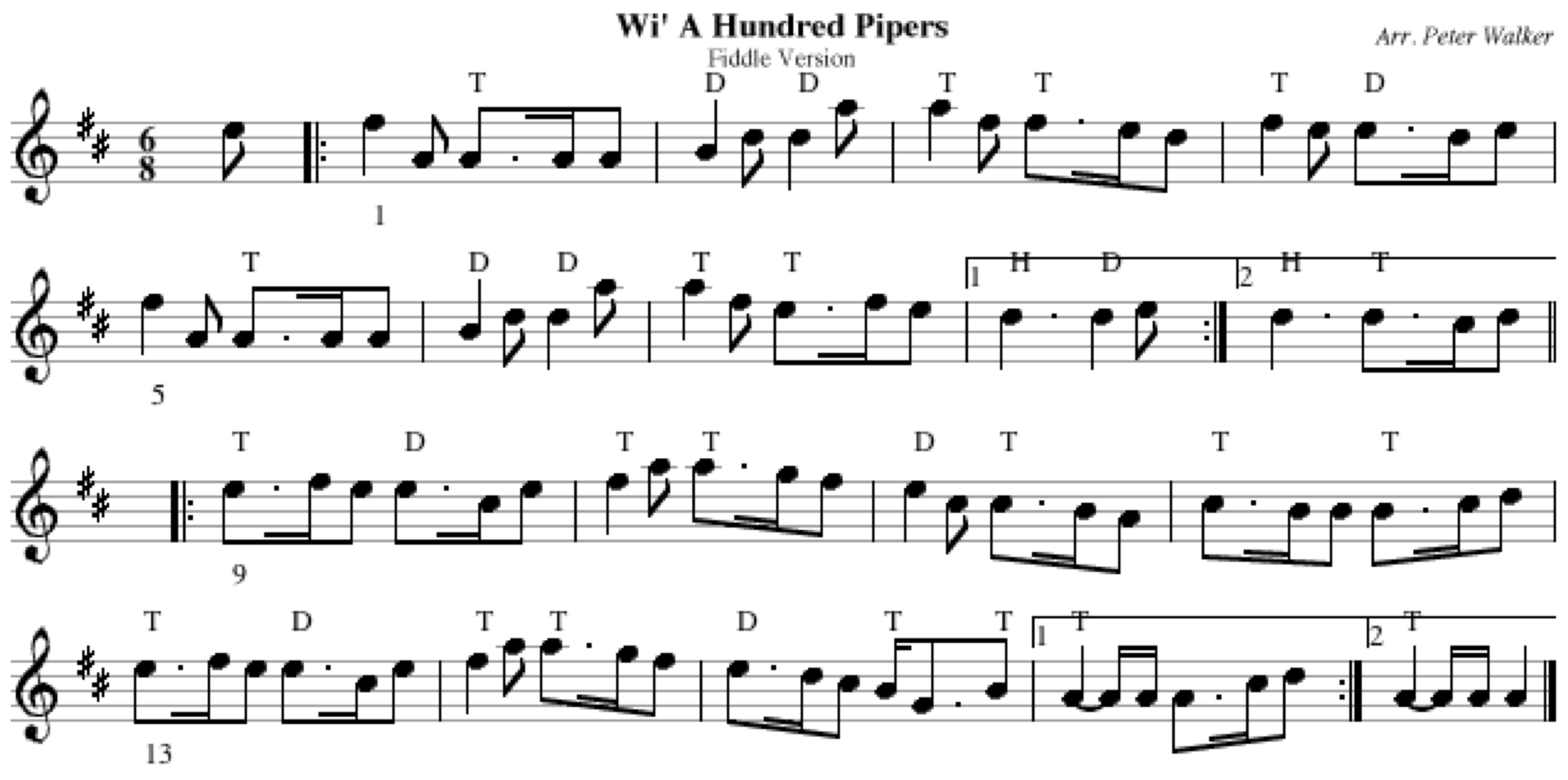

Pipes & Drums:

Let's first take note of the articulatory grace notes. There are numerous high

"g" gracings through the tune. These are single grace notes, or in the case of

grace notes between two high "a"s, echo beats. These serve to articulate the

adjacent notes, in some cases especially because they separate notes of the

same pitch. A fiddler could choose to adapt these with a tap on the beat, or

just an extra bit of pulse on the bow when changing notes. Note especially the

"d" grace notes in bar 15. The snap figure, ornamented like this ("g" grace note

before the sixteenth, "d" before the dotted eighth) is called a "tachum" in the

piping world. The extra articulation, beyond that already present in a snap, is

what makes this figure so characteristically pipe-like. Now I want to call your

attention to the emphatic ornaments. These begin with a "g" gracing, and follow

on with a second grace note delayed a bit after the beat. As discussed in previous

columns, this gracing serves to emphasize a note. We see doublings paired with

shakes in bars 2 & 6, doublings (the first beat of bars 11 & 15 and the second

beat of bars 4, 9, & 13), a shake in the second beat of bar 8. A fiddler might

emphasize these a bit more with a delayed tap.

Now comes the real fun! Look at the taorluaths in bars 1, 5, 11 & 12, and the

leumluaths in bars 9 & 13. Notice how they always occur between a quarter note

and an eighth note? If you'll recall my previous columns, these types of ornaments

take time from the previous note (in this case, the quarter), and take up

appreciable time. So what's happening here? Well, what you're really looking at

is a dotted eighth-sixteenth-eighth rhythm in disguise. The quarter note loses a

sixteenth's worth of time to the ornament, which becomes two 3nd low "g"s,

bisected by a "d" grace note, sometimes with an "e" grace note to the next melody

note. A fiddler would find a clever melody note to play in place of the ornament.

Finally, each part ends with an ornament. The first part ends with a d-throw, a

leumluath-like ornament that bubbles from low "g" through "c". I'd play that as

a hammer-on from "c" to "d". The second part ends with a birl, but not the kind

fiddlers are used to. It's a 2-pulse burl, basically stealing a little time from

the end of the first beat to give to the second.

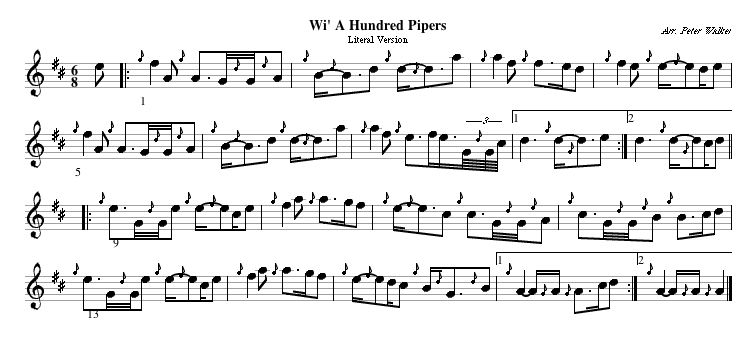

Here's what my "literal" rendering of this tune looks like.

What might the fiddle adaptation look like? Try it for yourself, and here's my take below!

4/4 Marches: Pointing the Way

We move now from the compound time, or 6/8 march, to the simple time, in this

case in 4/4. The vast majority of pipe marches one might hear performed by a

street band will be in 4/4 time, and though often composition- ally far simpler

than the 6/8 marches we’ve looked at previously, they do present their own

unique feature: a bending of the strict interpretation of time known as

“pointing.”

We should step back for a moment and remember that, while a reeded wind

instrument, the bagpipes do not allow for embouchure, not only because

the pipes are removed from direct contact with the airstream by the bag

(taking control of air velocity out of the equation), but because the bag

provides air to multiple pipes simultaneously, and any changes in pressure

will not only alter pitch as well as volume, but will do so differently

for the chanter and each of the drones, putting the pipes out of tune with

themselves (and any other instrument around them).

This puts the bagpipe in the awkward position of being incapable of stressing

particular notes in keeping with the meter or scansion of the music. The

bagpipe’s volume is fixed by the physics of the chanter: in the case of a

conical bore chanter like the Highland pipes, the lowest note is the loudest,

the highest note is the quietest, and there's nothing the player can do to

accent a given note (notably, cylindrical bore chanters like the smallpipes

reverse this volume profile - the highest notes are the loudest, and the

lowest the softest).

This means that all stress and accent on a bagpipe are implied, rather than

directly expressed. This is accom- plished by two methods. The first is by

emphatic ornamentation, such as single grace notes, or double-pulse emphatic

ornaments like doublings and shakes, which we have previously discussed.

But the second method uses a form of agogic stress where a dotted note is

given additional time at expense of the flagged note that follows it. This

is what is meant by “pointing.” The degree of pointing, that is, how much

of the flagged note is stolen by the dotted note, can vary to imply different

levels of stress, which we will see in 2/4 marches and strathspeys, but in

the case of 4/4 time, the general rule for pointing is “as much as possible!”

We hold the dotted note for as long as it can be held, and play the flagged

note as briefly as it can be played while still being perceived as a melody

note. Because the beat in 4/4 time is on the quarter note, the largest note

that can be pointed is the dotted eighth; a dotted quarter is not eligible

for this treatment, as it ends on the upbeat, which is generally inviolable

in pipe music. Pointing can occur in 6/8 time, but because in this case the

dotted eighth ends on the upbeat, the largest note eligible for pointing is

the dotted sixteenth. While pointing dot-flag pairs, one should remember

that even eighth notes are not played with any stress, but perfectly evenly;

it is the contrast between the highly pointed pairs and the perfectly even

pairs that makes the 4/4 genre of music to stand out.

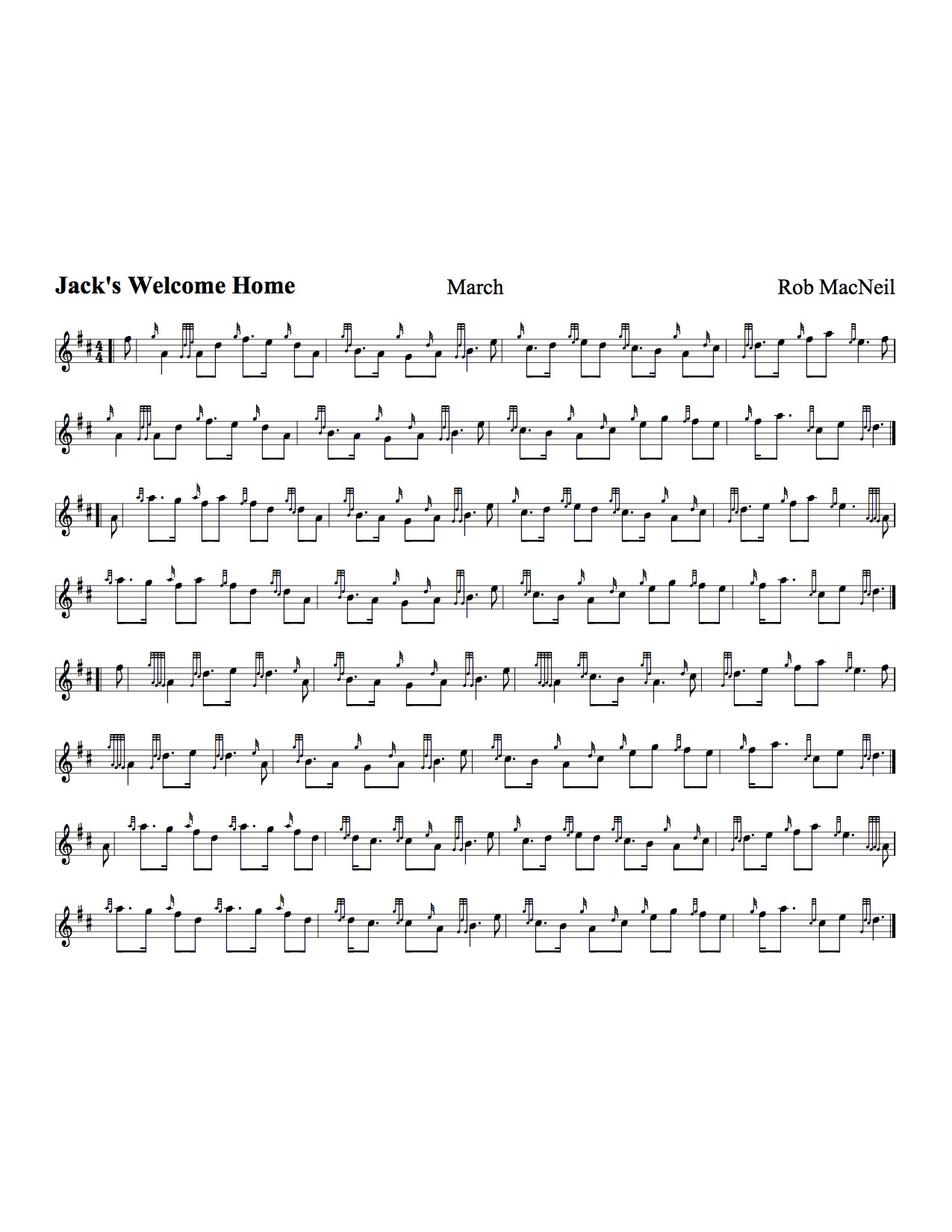

The tune I have given as an example is “Jack’s Welcome Home” by Rob MacNeil,

with the pipe setting used by City of Alexandria Pipes and Drums. The ornaments

used are typical of those seen in previous tunes. I do call your attention to

one figure, at the start of the second bar in lines seven and eight - a doubling

on a snapped figure. A doubling on a snap, seen frequently in strathspeys, is

meant to convey a triplet figure similar in timing to an open birl. Pointing

doesn't just affect dot-flag notes. As we have previously seen, semi-melodic

ornaments like grips and taorluaths often substitute for flagged notes, and

as such are often eligible for pointing. In this tune, the taorluaths in the

first and second lines of the tune are prime examples of this effect.

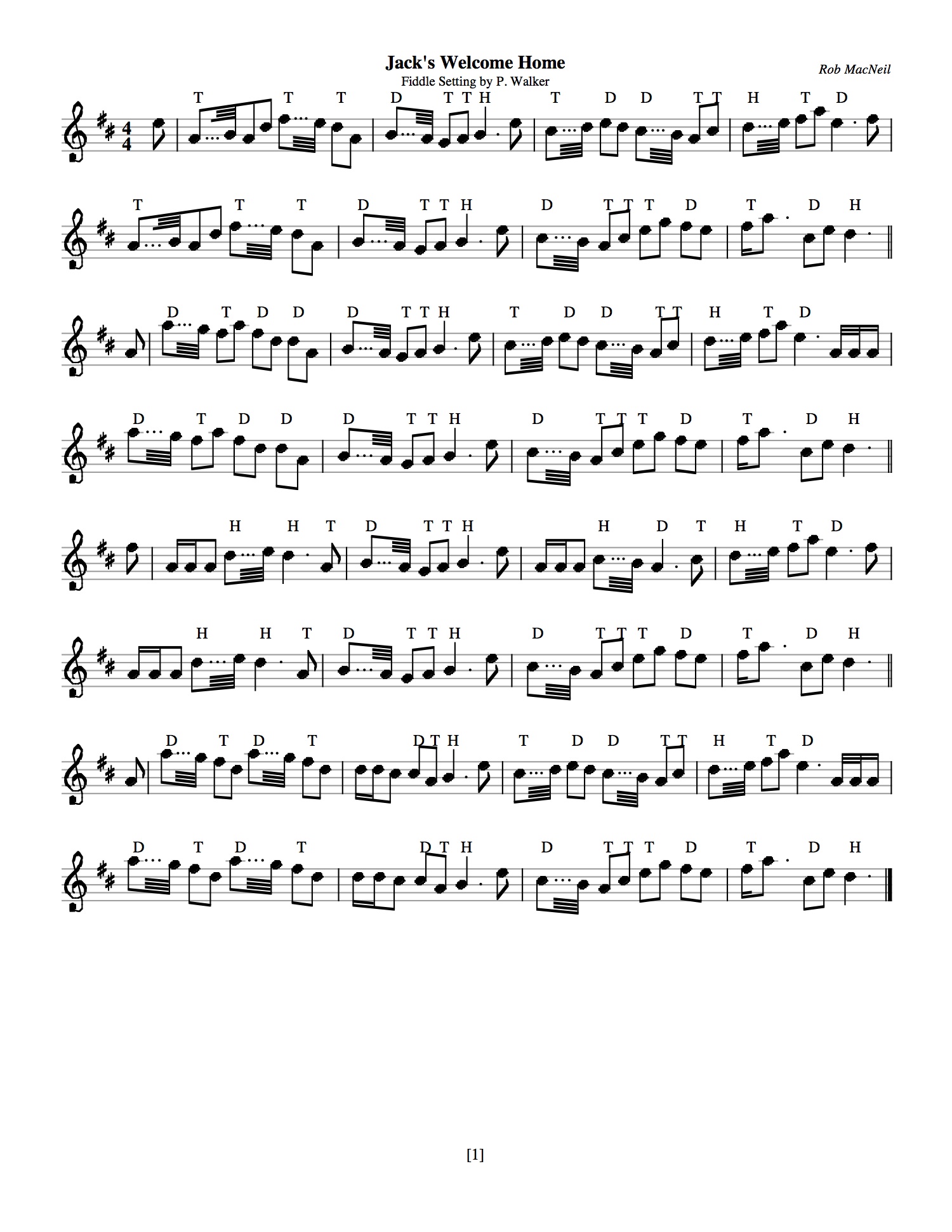

My attempt at a fiddle adaptation is at here, using my

standard convention of “T” for a tap on the beat, “D” for a delayed tap, and

“H” for hammer-on. I have notated the pointing by replacing the single-dotted

eighth notes with triple-dotted ones, though the timing is inexact, this

conveys the severity of the agogic stress used in a 4/4 march.

Oh, if you missed any of the previous columns, they're all up at the new website

location above! Soon I'll be adding embedded YouTube videos of the ornaments and

tunes being performed on the pipes and their equivalents on fiddle.